Truth, Power, and Text: A Cambridge Clash Over Postmodernism

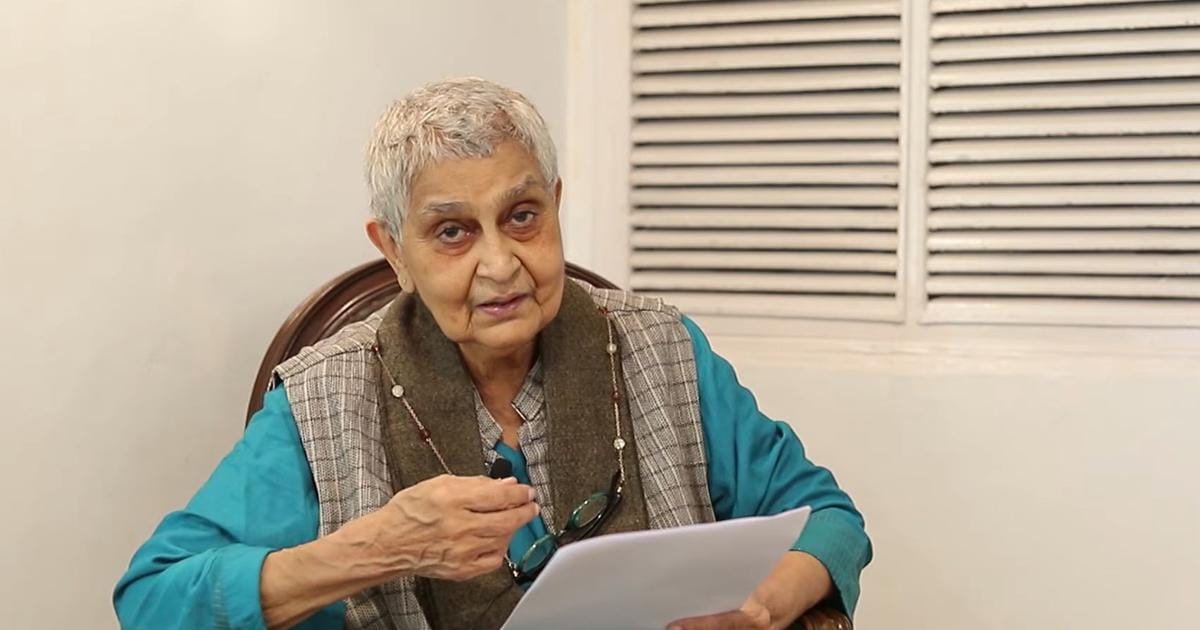

In a riveting debate at Cambridge, intellectual heavyweights Gayatri Spivak, John Dunn, and Ronald Aronson dissect the promises and pitfalls of postmodern thought.

In this compelling Cambridge debate on postmodernism, leading intellectuals Gayatri Spivak, John Dunn, and Ronald Aronson delve into the profound philosophical and political implications of post-structuralism. Their exchange illuminates the tensions between Enlightenment rationality, Marxist tradition, and postmodern skepticism. This debate is not merely academic; it explores the very tools we use to understand the world, question authority, and pursue justice.

Rejecting Absolute Truth: Postmodernism's Philosophical Foundation

The debate begins by examining the legacy of the Enlightenment. Western thought, since the Enlightenment, has operated under the belief that reason grants us direct, unmediated access to truth—both in nature and in human nature. This confidence underpinned ideas of progress, science, and emancipation. However, as the moderator notes, even contemporary defenders like Jürgen Habermas concede that the "modern project" remains incomplete.

The 20th century's horrors—totalitarian regimes, nuclear annihilation threats, ecological crises—have called into question whether reason alone can guide humanity. In response, post-structuralism, particularly in the hands of French thinkers like Michel Foucault and Jean-François Lyotard, proposes a radical skepticism toward the concept of universal truth.

Spivak on Deconstruction: Exposing the Silences of Narratives

Gayatri Spivak, a leading deconstructionist, articulates that post-structuralism does not declare war on narratives but exposes their limits. She argues that every narrative—especially those claiming to deliver justice—necessarily excludes alternative ends and voices. Post-structuralism is thus a "radical acceptance of vulnerability," an acknowledgment that no story is ever complete.

Spivak emphasizes that deconstruction is not the cessation of narration but a critical dance at the edges of narrative production. Post-structuralists, she argues, illuminate what is left out: the unsaid, the unrepresented, and the historically marginalized. This includes challenging the idea that history can be told as a seamless tale of progress or emancipation. For Spivak, "text" is not merely verbal language but a dense network of socio-political, psychological, and cultural inscriptions.

Marxism Under Postmodern Scrutiny

Ronald Aronson defends the analytical strength of Marxism while acknowledging its historical misuses, including its role as a state ideology. He underscores Marxism's self-critical capacity and its enduring value in understanding capitalist structures and global inequality. However, he concedes that Marxism must now contend with multiple forms of oppression—gender, race, colonialism—that it historically sidelined.

Spivak pushes further, noting that Marxist thought often privileges a male, Western, industrial worker as the universal subject. This universalism, she argues, is itself a narrative of exclusion. She draws attention to feminist and postcolonial critiques that reveal how class struggle narratives often marginalize peasants, women, and non-Western subjects.

Dunn's Rationalist Rebuttal: Defending Enlightenment Legacies

John Dunn offers a powerful counterpoint. He argues that while post-structuralist critiques are intellectually stimulating, they offer little practical help in confronting real-world threats like nuclear war. For Dunn, effective political theory must simplify reality to understand causal relationships. He worries that postmodernism's suspicion of truth and objectivity might undermine this capacity.

Dunn challenges the postmodern rejection of Enlightenment reason, asserting that the virtues of logic, honesty, and causal analysis remain essential. He concedes that all narratives are selective, but insists this does not invalidate the possibility of accurate or meaningful political judgment.

Political Practice and the Limits of Representation

The discussion turns toward what post-structuralist thinking means for political action. Spivak insists that we cannot assume political programs can ever fully represent justice or truth. She references Lyotard's concept of "regimes of truth" and argues for constant self-awareness of our narrative investments.

Aronson, in contrast, stresses that urgent political challenges—such as ecological collapse or global inequality—require more than theoretical skepticism. He supports historically grounded, structural analysis capable of being debated, tested, and improved. Yet he acknowledges postmodernism's role in broadening political theory's scope to include silenced histories and epistemologies.

The Text as World: Final Reflections

As the debate concludes, Spivak addresses the common critique that postmodernism reduces everything to text. She clarifies that "text" refers to a broader network of meaning, not just language. Even catastrophic events, she argues, are "textual" in that they emerge from historical and discursive contexts. Thus, the nuclear threat is not just material but also embedded in narratives of power, technology, and ideology.

Dunn remains skeptical, asserting that political progress requires cognitive clarity and objective analysis, not just narrative deconstruction. He worries that overemphasis on textuality might lead to political paralysis. Nonetheless, all participants agree on the necessity of continuous dialogue and the value of exposing blind spots in dominant ideologies.

Conclusion: Navigating Between Systems and Silences

This debate does not resolve the philosophical divide between rationalism and post-structuralism, but it models how they might coexist. Post-structuralism urges humility, attention to exclusion, and resistance to authoritative totalities. Rationalism, on the other hand, insists on clarity, objectivity, and the pursuit of truth as essential for political action.

Together, they suggest a middle path: one where critique and structure, vulnerability and clarity, history and its silences, can jointly inform how we understand and act in the world.

Reference