Technofeudalism and Marx’s Capital: A Modern Perspective on Digital Exploitation

In the digital age, the new class struggle is not just about wages—it’s about data, autonomy, and control over the digital commons.

Introduction

Karl Marx’s seminal work, Capital, laid the foundation for understanding the mechanics of capitalism—its reliance on labor exploitation, surplus value extraction, and the relentless drive toward accumulation. However, with the rise of digital monopolies and the phenomenon that Yanis Varoufakis terms technofeudalism, the economic landscape has evolved in ways that Marx could not have anticipated. Yet, the core dynamics of power, control, and exploitation remain eerily similar. This article explores how Marx’s concepts from Capital help us understand the transition from industrial capitalism to a new form of digital feudalism.

1. Surplus Value in the Age of Digital Labor

Marx identified surplus value as the key mechanism by which capitalists extract profit from labor. In traditional capitalism, surplus value is generated when workers produce goods for capitalists who sell them at a price higher than the wages paid to laborers.

In technofeudalism, surplus value is extracted in non-traditional ways:

- Unpaid Digital Labor: Users of platforms like Facebook, Google, and TikTok generate content, data, and engagement—all of which create value for the company while the users themselves are unpaid.

- Algorithmic Manipulation: AI-driven platforms optimize engagement to maximize advertising revenue, effectively extracting attention and behavioral data from users as an unpaid form of labor.

- Digital Rent Extraction: Instead of making profits through commodity production, companies like Amazon and Apple collect digital rent—charging businesses for access to their platforms, akin to a feudal landlord collecting dues from serfs.

In this system, value is extracted not just from direct labor but from passive participation in digital ecosystems, making it a novel yet fundamentally exploitative evolution of surplus value theory.

2. The Disappearance of the “Free Market”

Marx argued that capitalism relies on competition to regulate prices and drive innovation. However, he also warned that capitalism tends toward monopoly as firms seek to dominate markets.

Today, we see the fulfillment of this prediction:

- Tech Oligopolies: Companies like Google, Amazon, and Apple function not as participants in a free market but as gatekeepers that determine which businesses can operate within their ecosystems.

- Platform Capitalism vs. Market Capitalism: Instead of competing within a market, businesses now must pay fees and comply with platform rules dictated by the tech giants.

- Financialization of Tech Capital: Unlike industrial capitalism, where capital was reinvested into production, tech giants primarily engage in financial engineering—buying back stocks, leveraging tax havens, and using their market power to extract rent rather than create new value.

In effect, capitalism’s central pillars—markets and competition—have been replaced by platform monopolies and digital serfdom.

3. The Return of Feudal Power Relations

In Capital, Marx described capitalism as distinct from feudalism because workers were nominally free—they could sell their labor to any employer. However, in technofeudalism, workers and consumers are increasingly tied to digital lords who control access to economic participation.

Similarities Between Feudalism and Technofeudalism:

- Serfdom in Digital Form: In medieval feudalism, peasants worked the land owned by lords. Today, businesses and consumers operate on digital land controlled by tech giants.

- Surveillance Capitalism as Social Control: In the feudal era, landlords controlled people through land ownership. Today, AI and data analytics allow tech lords to predict and influence user behavior, shaping social and political outcomes.

- Rentier Economy Instead of Wage Labor: Instead of wages, many people today survive in gig economies controlled by algorithms (e.g., Uber, Amazon Mechanical Turk), where they work under precarious conditions dictated by unseen digital landlords.

Marx believed capitalism would evolve into socialism through class struggle. Instead, it has evolved into a system where control over digital infrastructure has replaced control over physical production.

4. The Role of the State in Technofeudalism

Marx emphasized the role of the state in protecting capitalist interests. Under technofeudalism, the state plays a similar role in enabling and legitimizing the power of digital monopolies.

- Bailouts for the Digital Lords: During economic crises (such as the 2008 financial collapse and COVID-19 pandemic), governments provided massive financial aid to corporations like Amazon and Google while leaving smaller businesses to struggle.

- Weak Antitrust Enforcement: Regulatory bodies have failed to prevent tech monopolies from growing stronger, reinforcing a winner-takes-all dynamic.

- Data Ownership and Surveillance: The state increasingly collaborates with tech companies to harvest and control data, using it for mass surveillance, law enforcement, and even political suppression.

Thus, instead of acting as a neutral arbiter, the modern state functions as an enforcer of digital feudalism, much like feudal kings legitimized the power of lords.

5. Resistance: Can Digital Workers Reclaim Power?

Marx believed that workers, through collective struggle, could dismantle capitalist exploitation. However, in the digital economy, resistance must take new forms:

- Data as a Public Good: If surplus value in technofeudalism is extracted through data, users should collectively own and control their own data.

- Decentralized Platforms: Alternative models such as open-source software, decentralized web platforms, and cooperative tech initiatives can challenge digital monopolies.

- Algorithm Transparency & AI Ethics: Demanding transparency in how algorithms manipulate behavior and extract value is crucial to breaking the control of digital landlords.

- Digital Unionization & Collective Bargaining: Just as industrial workers formed labor unions, gig workers, digital freelancers, and content creators must organize to demand fairer conditions in platform economies.

Conclusion: Marx Was Right, But the System Has Evolved

While Marx described capitalism as a system that continuously reinvents itself through crisis and adaptation, he may not have foreseen that capitalism would morph into something arguably more exploitative—a system where human autonomy is shaped not just by labor exploitation, but by digital enclosure, behavioral engineering, and AI-driven rent extraction.

Technofeudalism does not replace Marx’s insights—it extends them into a new epoch where control over digital capital has replaced control over industrial capital. If Marx’s Capital remains relevant today, it is because it provides us with the tools to analyze who controls the means of digital production—and how we might reclaim them.

In the digital age, the new class struggle is not just about wages—it’s about data, autonomy, and control over the digital commons.

Reference

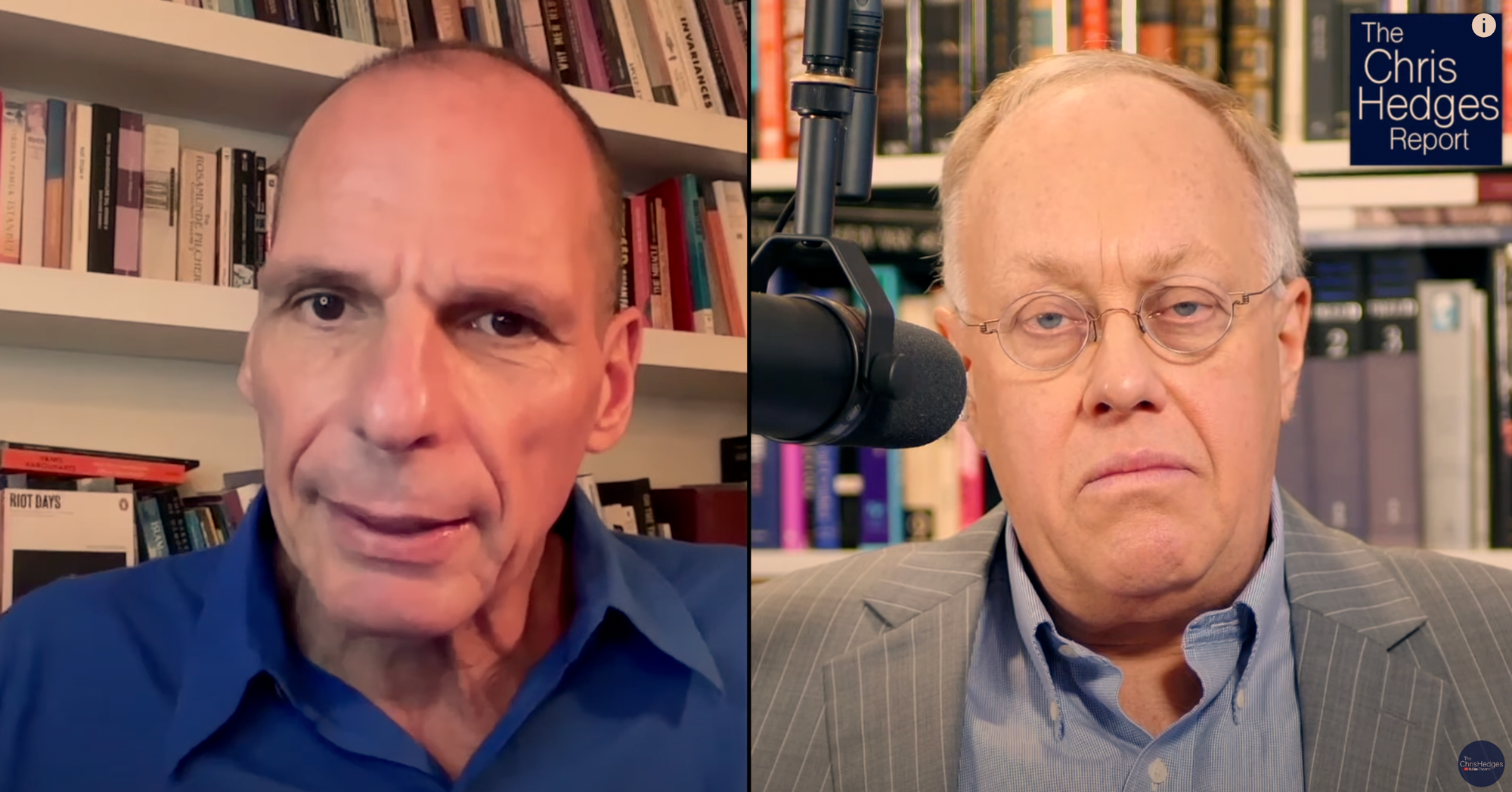

YouTube video: Technofeudalism: What Killed Capitalism (w/ Yanis Varoufakis) | The Chris Hedges Report