Structure, Sign, and the Game of Meaning

Meaning is not static, but emergent. The “play” of structure and sign is not chaos, but a dance—one that invites us to read the world not as a fixed text, but as a living, shifting constellation of signs.

In the realm of deconstructionist philosophy, Jacques Derrida’s seminal lecture “Structure, Sign, and Play in the Discourse of Human Sciences” marks a critical turning point. Delivered in 1966 at Johns Hopkins University, this text challenges the stability of structuralism by proposing a dynamic, fluid conception of meaning. Derrida’s concept of “play” disrupts the traditional notion of a fixed center that guarantees meaning. Instead, he posits a world where meaning is perpetually deferred—what he famously terms “différance.”

To understand this abstract theory in more tangible terms, Wallace Stevens’ poem “Anecdote of the Jar” serves as a poetic illustration. The poem narrates how a single jar, placed upon a hill in Tennessee, subtly transforms the landscape around it. Nature, once wild and unordered, becomes shaped by the presence of this artificial object. The jar doesn’t impose meaning in a rigid sense—it reframes the environment, inviting a shifting interplay between the object and its surroundings.

Here, we see Derrida’s “play” in action. The jar is not a fixed center but a relational marker—it organizes yet simultaneously destabilizes the field of interpretation. The landscape becomes legible not through intrinsic order, but through the relational positioning of the jar within it. Meaning, as Derrida might argue, arises not from essence but from structure—and that structure is itself in motion.

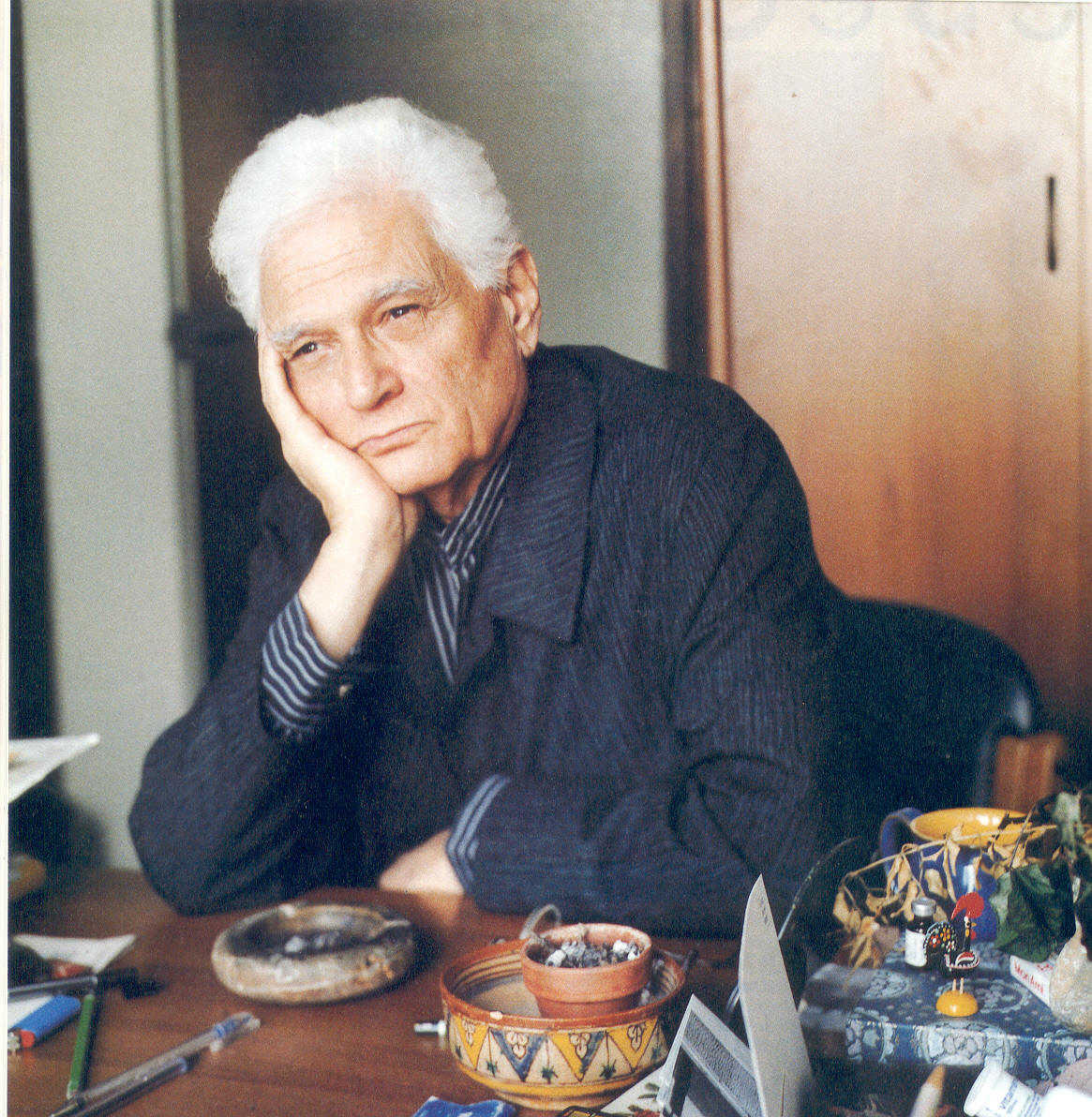

This conceptual resonance is further illuminated in the Yale Open Course lecture on literary theory by Professor Paul H. Fry. In his discussion of deconstruction, Fry emphasizes that Derrida does not seek to destroy meaning or structure but to uncover the mechanisms through which meaning is produced, often through the illusion of stability. Stevens’ jar exemplifies this process: it is both arbitrary and transformative, revealing how human symbols condition and reconfigure the natural world.

Fry underscores that deconstruction is not nihilism—it does not claim there is no meaning, but rather that meaning is always in process. The jar in Stevens’ poem becomes a metaphor for all signifiers: seemingly central, yet endlessly deferred in their capacity to signify. Just as Derrida dismantles the illusion of a fixed philosophical center, Stevens poetically gestures to the same insight—the center does not hold because it was never truly there.

The Eiffel Tower, another man-made symbol looming over a natural and historical landscape, might also be read in this light. It dominates yet does not define Paris; it symbolizes modernity, surveillance, and national pride, but none of these meanings are stable. Like the jar, the Tower is an architectural “signifier” whose meanings are multiple, contested, and dependent on context—a structure that plays in the Derridean sense.

Ultimately, Derrida, Stevens, and the reflections from Yale converge on a shared truth: meaning is not static, but emergent. The “play” of structure and sign is not chaos, but a dance—one that invites us to read the world not as a fixed text, but as a living, shifting constellation of signs.

References

1.Derrida: ‘Structure, Sign and Play in the Discourse of the Human Sciences’ (1966/trans. 1970) The Structuralist Controversy: The Languages of Criticism and the Sciences of Man (Johns Hopkins)

2.Deconstruction Lecture: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=Np72VPguqeI